Expectations, Values, Expected Values

What's the Value of a Win

Money can buy you a lot in sports.

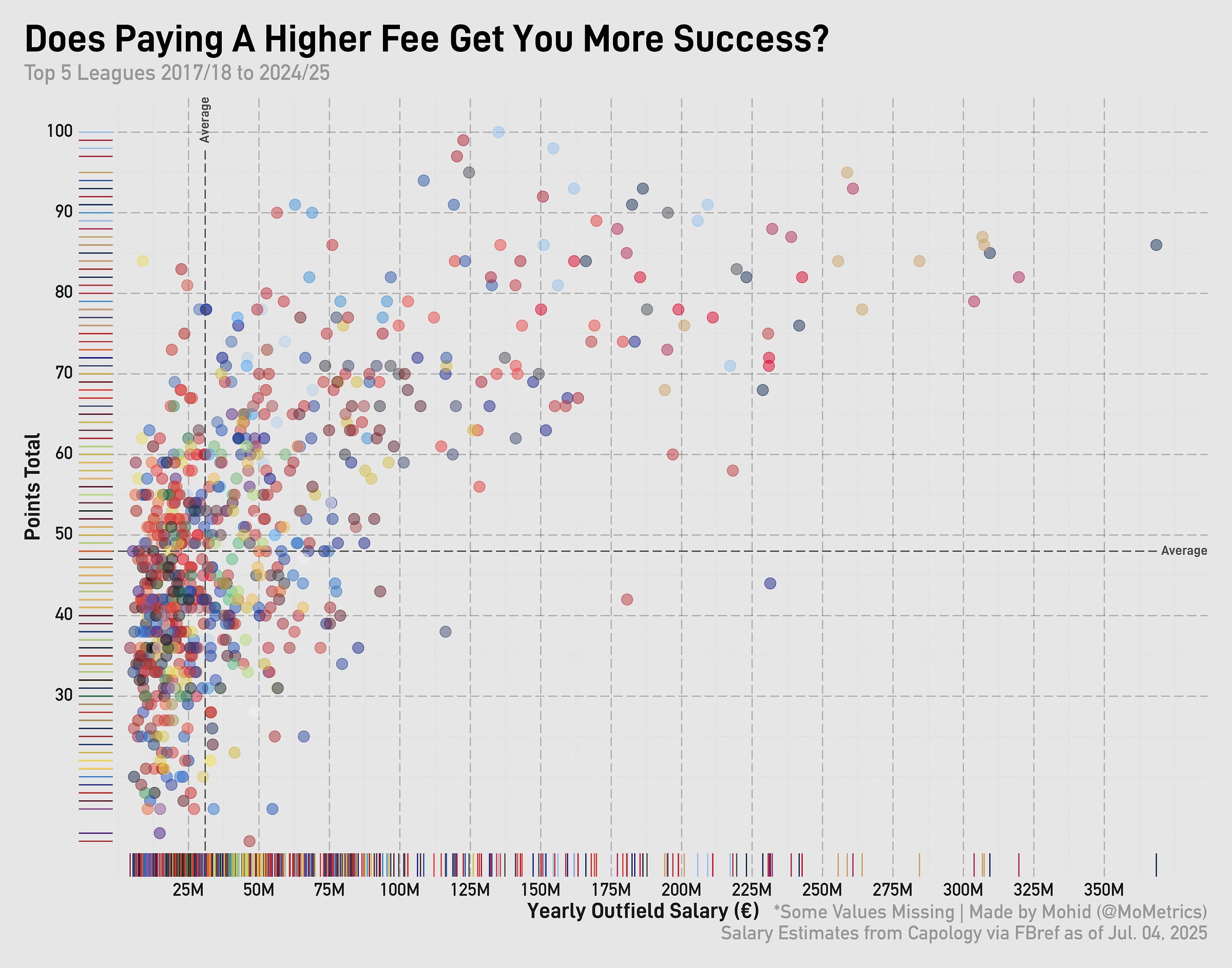

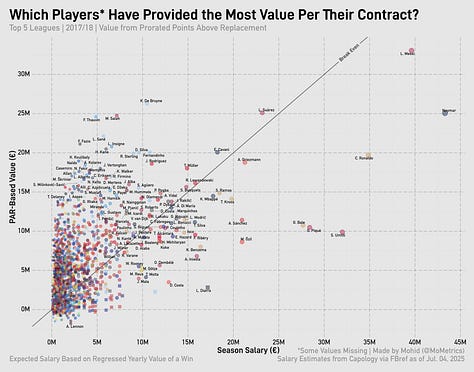

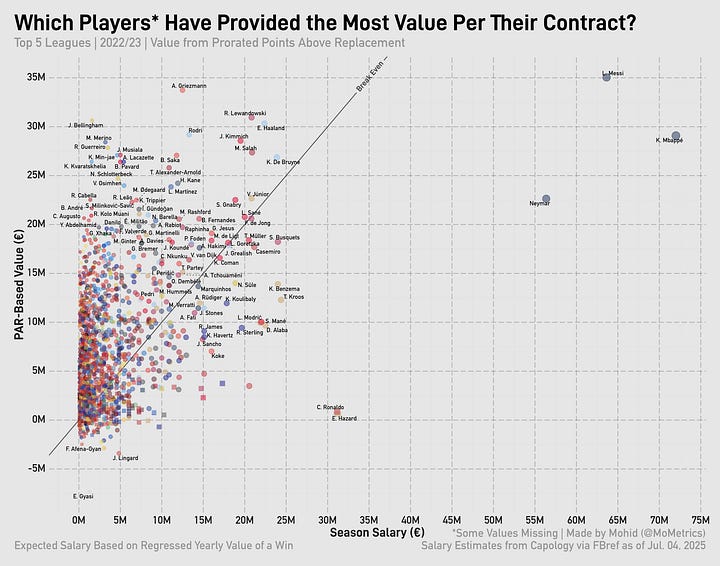

Take a look at this chart:

This shows you how much teams have paid in yearly salaries based on estimated data by Capology and presented through FBref1. It’s only for outfielders, but there’s a distinct correlation between the salary you pay and the points you get.

It’s a weird-looking correlation, though. Distinctly logarithmic. That just shows there are diminishing returns in the business. Particularly at the top end when you get past 150m Euros in yearly pay.

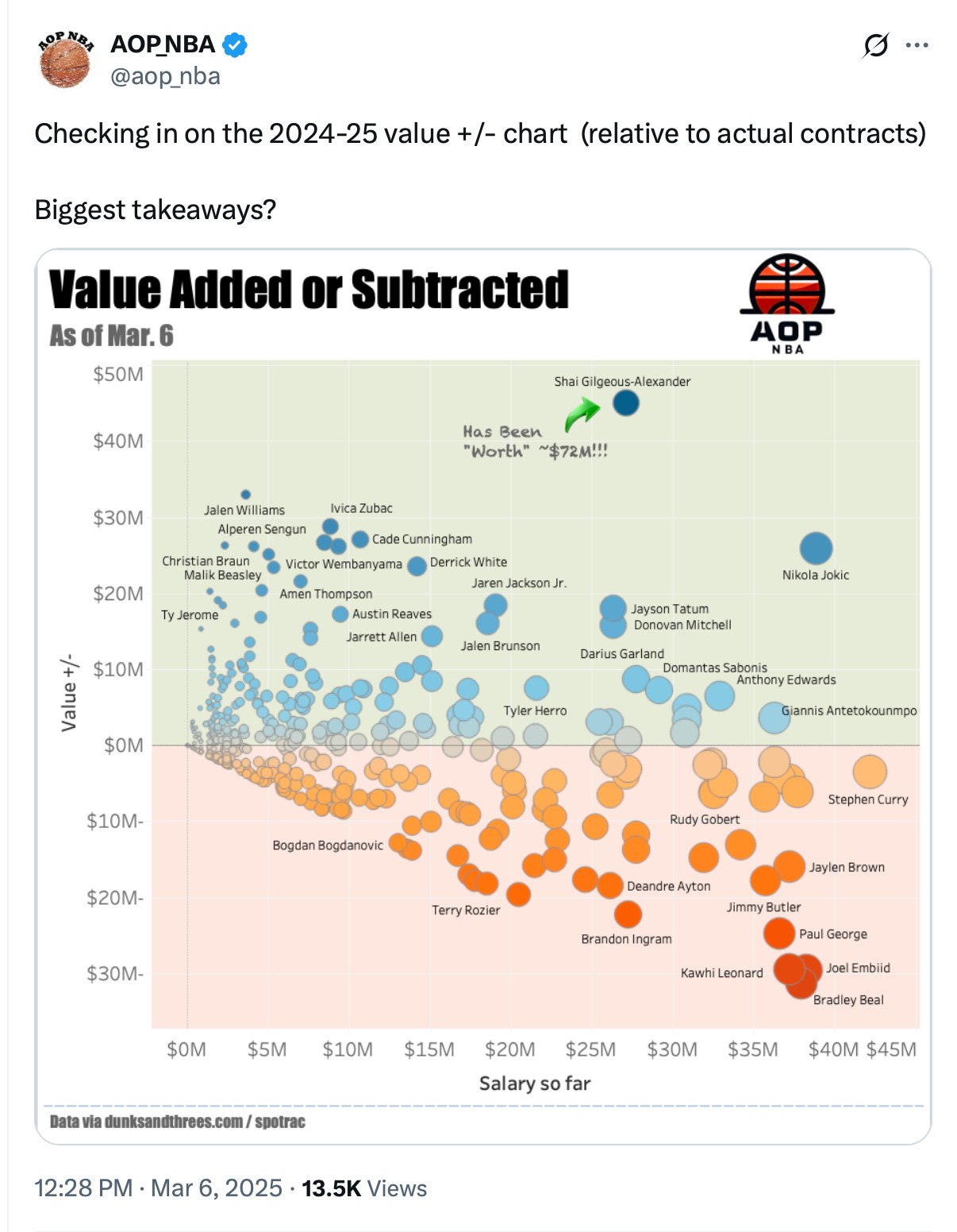

What I want to find out here is whether soccer higher ups tend to pay their guys properly. My curiosity is largely inspired by this tweet:

There are a couple things that make this somewhat simpler to do in basketball when compared to football. For one, basketball has a salary floor. So even if every team only paid at that level, there’d still be disparities in the winning totals and the cost per win would stabilize around a representative value on a per-player basis. Second, the salary cap prevents certain teams from overspending for mediocrity.

Look at the graph at the top, again. The darkish-blue dots on the far right are PSG, and they spend quite a bit of money to not have the best-of-the-best points totals.

Take their 22/23 season, for example. They spent around an estimated €310m, where ~€192m was invested in three players (Mbappé, Messi, and Neymar, in order). That €192m was meant to lead to a treble or better in Paris. Based on money alone, you’d expect this front three—on their own—to put up a points total that rises into the low-90s. But that’s not necessarily the case. They only earned 85 points in the league and were knocked out in the round of 16 of the UCL.

Overall, in the league (and I’ll explain why I’m isolating this in a sec), PSG paid almost €11m per 3 points (or the points-equivalent of a ‘win’). If we look at the NBA that same season (22/23), it paid $4,722,070,342 per Spotrac for a total of 1230 wins, which comes out to $3,839,081 per regular-season win (which is why I’m comparing league-game win values).

That makes you think a win in soccer is worth so much more, right? Not really. Again, go back up to the top graph and look at the ‘rug’ plot on the bottom. Most team salaries are concentrated between €0-€100m. Taking the win totals among all teams in 22/23 to spend less than or equal to €100m on their wage bill and dividing it by their ‘win’ totals (pts/3), you get each win being worth around €1,844,741. But if you look at all the teams that spend more than €100m, that pay per win ends up being €7,150,428. That’s a pretty big disparity. especially since overall the value per win is €2,856,928 (across 2017/28 to 2024/25). The issue here is that teams with big wage bills have . . . big wage bills.

It’s the slight issue of the salary floor (and cap) where worse teams can’t afford to fork over as much money as the big teams. This means they have to find cheap talent that still ends up being good.

Lens were the biggest outlier we’ve seen in the modern data era, winning 84 points on an estimated €8,740,000 (outfield) payroll. In other words, PSG paid more than €300m for one (1!) more point—roughly speaking. So when we try to find the ‘value of a win,’ it’s tough to eke out something amidst the noise.

The next two sections are all methodology. If you don’t want to read all that, just skip to the section titled “Player Data”

Creating Points

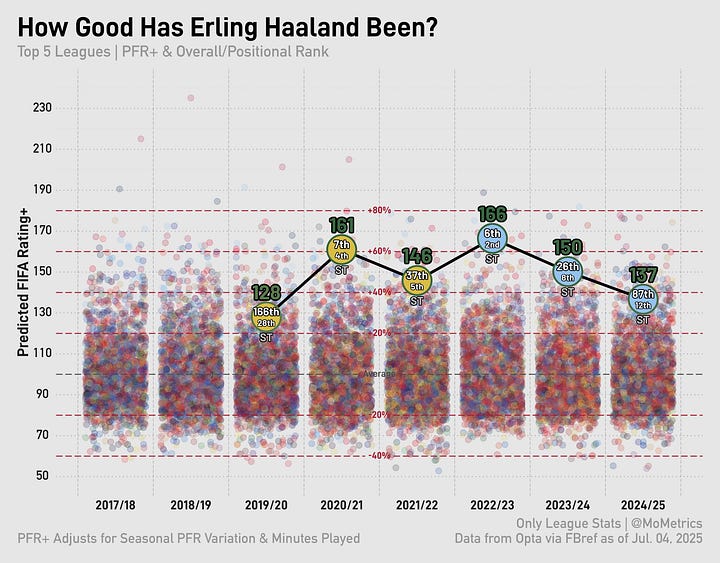

Just a quick disclaimer: the values I present are purely theoretical and largely estimated. Soccer’s a very dynamic game with multiple outcomes per play and game, which is quite unlike other sports. Because of this, it’s hard to measure estimations of individual player quality/value/importance (particularly without match-level data). Nevertheless, the data I present is somewhat adapted from FanGraphs/Baseball Reference Wins Above Replacement and serves to try and isolate player importance.

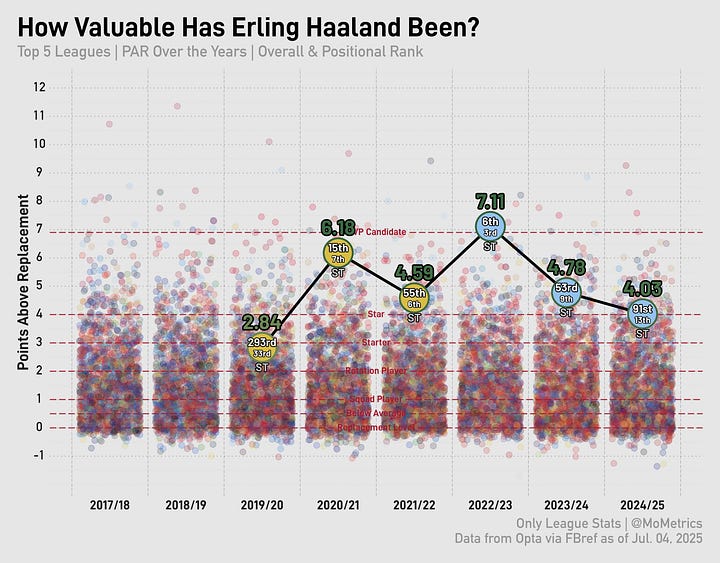

I’ve recently devoted a lot of time towards developing a Points Above Replacement (PAR) formula for soccer that I’m somewhat proud of (which means I hate it quite a lot and love to change everything about it every couple days).

PAR is built on the foundations of baseball, and at the core of the stat are goals. Goals = Points, simply put. The more you contribute, the more points you have to your name.

I’ve experimented with so many different manners of establishing the replacement-level, but the cornerstones of my approach have included three main ‘goal’ stats: actual goals and assists, not-actual VIBES2, and an estimate of goal difference effect through defense (probably the weakest link in the trio and one I had to ‘artificially’ boost a bit to make matter more in the totals).

This part is gonna be a little technical and will just detail the different ways I tried to create replacement-level

1) My first approach was to use the 10th percentile by position within the year. I liked this as I felt it was a simple way to conquer both positional spread and year-to-year variation, but I found this to not be that effective, overall. For one, the 10th percentile for actual goals amongst every position bar AM/W and ST was 0, so it literally was not changing that total whatsoever.

2) I tried finicking with the goals per point value a bit. I included goals scored, assists provided, and VIBES created (but left out defensive influence as I felt that was doubly included in the data—a goal scored is a goal conceded, y'know). The goals per point I've settled on is around 4-5, which I think is a good-ish value. I compare it to baseball which ranges from 9-10 yearly, and in which case that's 9 runs per win and thus 3 runs per point (if baseball used W = 3, D = 1 scoring).

3) What I've finally settled on (for the time being) is mimicking Baseball Reference and FanGraphs in using goals above average, incorporating a league & position factor, and then tacking on 'replacement goals' to boost a player from PAA (Points Above Average) to PAR. I'll dive into this right now:Establishing replacement goals was a little tricky. What I found was that a team of players in the 10th percentile (amongst qualified players3) playing a 4-2-3-1 (so 2 FBs, 2 CBs, 1 CM, 1 DM, 1 AM, 2 Ws, and 1 ST) would rack up a theoretical 23 points over the course of a 38-game season. So I set my replacement level at 23.

Finding the number of replacement runs to go around was a little difficult. I settled on using this formula present on Baseball Reference’s explainer on PAR:

Teams * Games per Team * (0.500-Winning Percentage of Replacement Level)In this case, there are either 96 or 98 teams (Ligue 1 switched to 18 teams in 23/24) and then 38 or 34 games per team (Bundesliga & Ligue 1 have 34 games) and then the ‘winning’4 percentage of replacement level is 23/114 or 0.201754. I get that this is lower than baseball’s 0.294 but that’s for a good reason.

Football doesn’t have a salary cap or floor and is spread across 96/98 teams (compared to baseball’s 30). So the lowest of the low in football are worse off than the lowest in baseball. 23 points is also the total that every team but two has passed in Expected Points5 in the data era.

The replacement goals come out to 2,820 for a 96-team season and 2,940 for a 98-team season. I split this as 90% going to outfielders and 10% going to goalkeepers based on the proportion of overall minutes played by goalkeepers relative to all players. You give out replacement goals by first turning it into a proportion of goals available depending on how much of the season has been finished and then converting it to goals per 90 and multiplying by player 90s played. It can lead to around three points being added to a player’s PAR total based just on how much they play. This is because a player who’s average at creating goals but plays a lot of minutes is obviously worth more than a replacement-level player. This adjustment also makes it quite difficult for a player who plays a lot of minutes to be less than replacement-level—those guys are just plain bad.

PAR (when you add 23 to the total value at a team level and prorate both PAR and Pts to per-38 games) actually correlates better with xPts (R-squared = 0.9877) than Pts (R-squared = 0.976) but matches up better with Pts in terms of one-to-one correlation (coefficient = 0.93710, xPts coefficient = 0.924772). It’s not a perfect relationship between PAR and Pts, though. This is because of the nature of luck in soccer where a team that ‘deserves’ to win can often end up losing a lot—this is why each PAR is worth less than an actual point: it incorporates the luck factor.

The above R-squared values (and coefficients) are achieved when placing PAR (+23) as the independent variable without an intercept and regressing it to actual points.

The equation is:

Points ~ Total PAR + 0

I set the intercept at 0 because I want to isolate the effect of PAR on points and assume that only PAR on its own is responsible for changes in points. Otherwise, you shouldn't really remove the intercept when regressing (unless, as mentioned, you're trying to isolate or assume there is an isolated effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable).

The R-squareds without removing the intercept for both are:

Points - 0.8064 (coefficient: 1.2043)

xPoints - 0.791 (coefficient: 0.88745)

That's a lot less than before but it's still a very significant correlation. You can take either number—they're both worth something.

Side note: the intercept of xPoints actually ends up being way less significant, potentially aiding the idea that PAR and xPoints have a stronger relationship than PAR and Points. This makes sense—WAR and the Pythagorean winning formula in baseball have a stronger correlation than WAR and actual wins above replacement-level.As an example of PAR’s representability, Sheffield Utd in 2023/24 had 6.43 PAR but finished on 16 Pts and 30.76 xPts (the PAR Pts would be 6.43 + 23 or 29.43 total). You can attribute some of that misfortune to just how the game falls. WAR is not one-to-one in baseball, either. It’s just really close.

Valuing Points

I’ve already touched on this, but the value of a win is deeply affected by teams that end up paying quite little (relatively) and getting quite a lot. The mean Pts per 38 games amongst teams with a payroll under/equal to €100M6 is 48.5 (median = 47, n = 6787) and amongst those paying more than that is 78.3 (median = 79.9, n = 98). The median yearly salary is actually €30.9M (mean = €51.5M). If we use the median to split, the values come out like this:

Under/Equal to €30.9M = mean - 43.7 Pts per 38; median - 42.7 Pts per 38

Over €30.9M = mean - 60.9 Pts per 38; median - 61.2 Pts per 38

Lotta numbers. Basically, the amount of money you spend does matter, but there’s so many teams spending ‘low’ money that if you use the literal value of a point (the sum of salaries divided by the sum of pts), it’s going to, obviously, be bogged down. We need to find the value of a point beyond just what you might get by paying minimally.

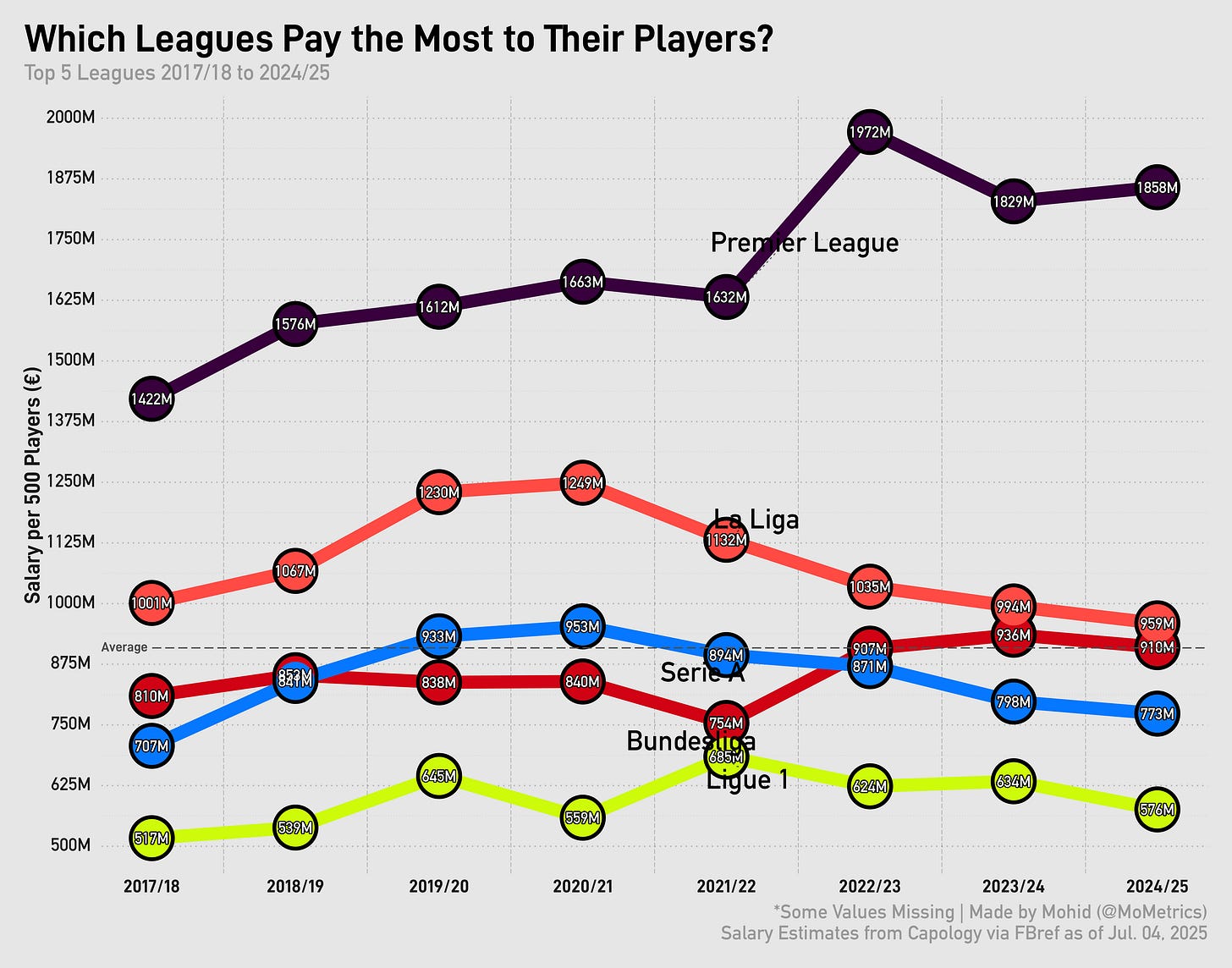

This value differs between leagues, too, but we equalize it to fairly reflect players’ contributions, no matter the spending power of the league (or team) that a player is in. Look at this chart to see the Premier League’s spending power relative to the rest of the leagues (adjusted to per 500 players to level the number of players per league):

The Premier League has gotten farther and farther clear of the rest in terms of the money it can spend, and was the only league alongside La Liga to spend a billion Euros in salaries this past season.

Now, with technicalities out of the way, here’s what I ended up doing to measure the value of a win:

Again, a lot of technical stuff in the technical-looking box. You can skip below this for the raw values and the player-level analysis.

I'm not a statistician, so take what I say with a grain of salt.

I tried several ways of trying to find the value of a point. I've changed this PAR model from a WAR model to a PAR model and I've tinkered with the insides of it so much I can't even remember what it looked like at the beginning. All of this has been to better mimic the actual points above replacement-level that teams get.

Because of this, I'm fairly confident in taking a simple regression of PAR summed up by team and comparing it to the salary of that team (having prorated the PAR to a 38-game sample).

The formula for that looks like this:

lm(Yearly Salary ~ Team PAR) but weighted by the percent of the overall salary that a team contributes. For 24/25, the highest contribution was Real Madrid at ~5% of all salaries in the top 5 leagues.

This spits out this summary:

Weighted Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-21370088 -3629407 -1535445 42875 51840883

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -57328057 6169328 -9.292 <2e-16 ***

Total PAR 3838027 132264 29.018 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 5989000 on 774 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.5211, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5204

F-statistic: 842 on 1 and 774 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

What this means is:

1) It's fairly good at estimating annual salary based on PAR totals (R-squared = 0.5204)

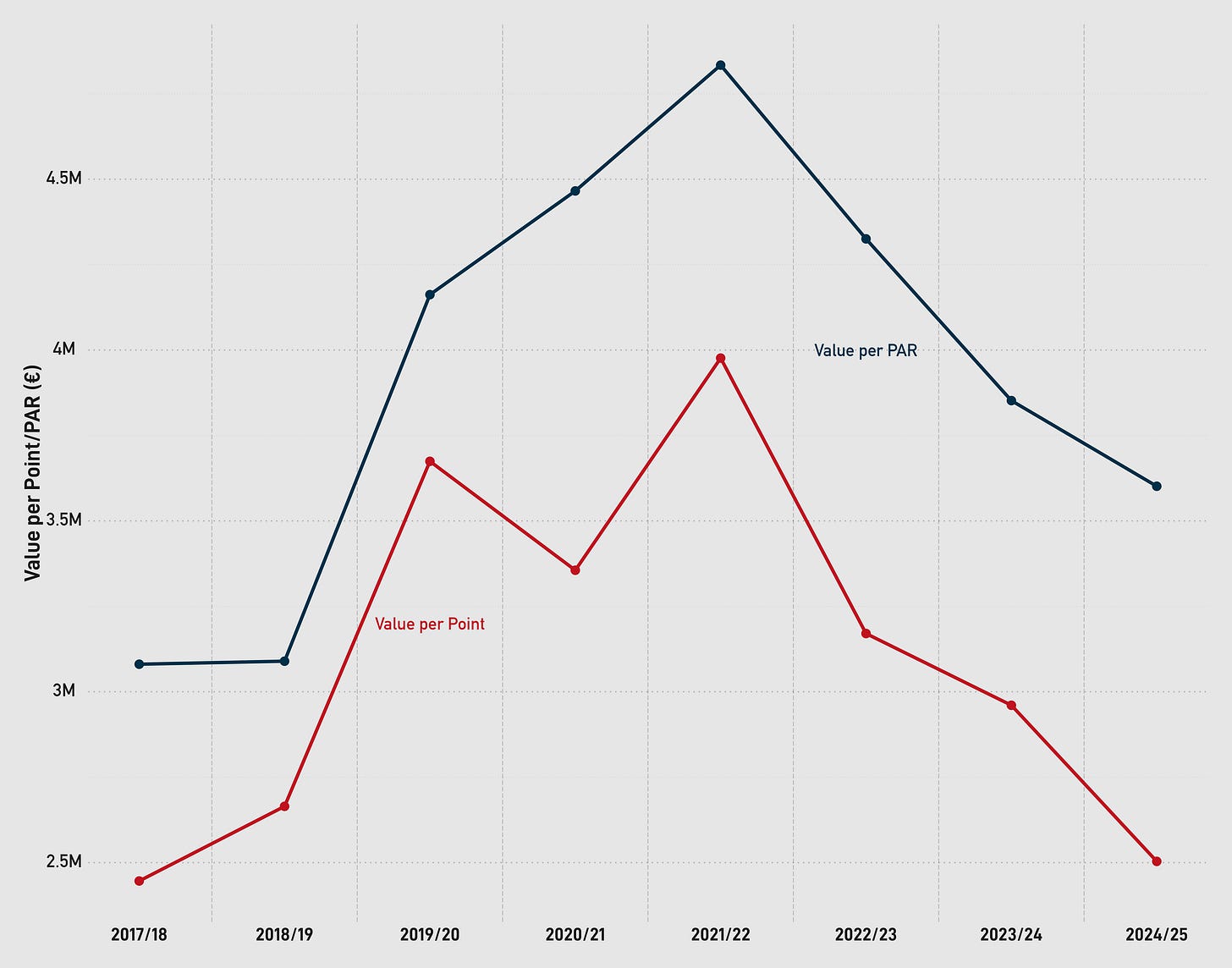

2) Each PAR is worth around €3,838,027 (for all seasons 17/18 to 24/25)

3) The intercept being -€57,328,057 means a team at replacement-level (0 PAR) would be expected to pay that much. That, of course, doesn't make sense. However, that's because there's no team that's been at replacement-level (based on the data—there have definitely been teams with 23 points or less, Sheffield Utd above).

3.1) The intercept doesn't really mean much here. It's just an estimate that needs to exist for the line to fit through.

I can run through a couple examples of the application of this equation. If I take the team with the lowest PAR with a recorded salary—Sheffield Utd 23/24 at 6.052411 paying €26,980,780—and use the regression equation:

(6.052411) * 3838027 - 57328057 = -€34,098,740 Estimated Yearly Salary

It breaks a little because of how much a win is worth in the Premier League (higher annual salaries, the whole chart above, and so on).

But (6.052411) * 3838027 = €23,229,316 Estimated Yearly Salary

Moreover, if I take a middle of the pack PAR total (Getafe 18/19, 29.37199 PAR, €15,912,000 yearly salary), that equation looks like:

(29.37199) * 3838027 - 57328057 = €55,402,433

That overshoots.

But (29.37199) * 3838027 = €112,730,490 (The equation without the intercept works better in cases when the final result with the intercept would be negative)

The issue here is that salary and wins comes with a logarithmic relationship. If I run the regression with logged salary values, here's the outcome:

Weighted Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.17687 -0.05763 -0.03630 0.00443 0.28055

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 16.379963 0.064257 254.91 <2e-16 ***

Total PAR 0.041000 0.001378 29.76 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

Residual standard error: 0.06237 on 774 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.5337, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5331

F-statistic: 885.8 on 1 and 774 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

The R-squared is already better, for one.

Sheffield Utd 23/24:

(6.052411) * 0.041000 + 16.379963 = 16.628 Logged Estimated Salary

exp(16.628) = €16,651,319 (actual being €26,980,780)

Getafe 18/19:

(29.37199) * 0.041000 + 16.379963 = 17.584 Logged Estimated Salary

exp(17.584) = €43,314,586 (actual being €15,912,000)

The values here are a little more accurate, but you can't really apply them to player-level PAR as the intercept is necessary to get reasonable non-logged numbers. These estimates are better representatives of the salaries these teams should be offering based on their players' contributions in a world where they all had the same money to offer.I took the coefficient of the linear regression of PAR to salaries for each season to establish the baseline value per win per season.

I also ran it for value per point (above replacement, so Pts - 23). Teams tend to pay more per PAR from players than the actual points above replacement they procure, but the intercept of the regression of Value per Point is a smaller negative than that for Value per PAR.

Player Data

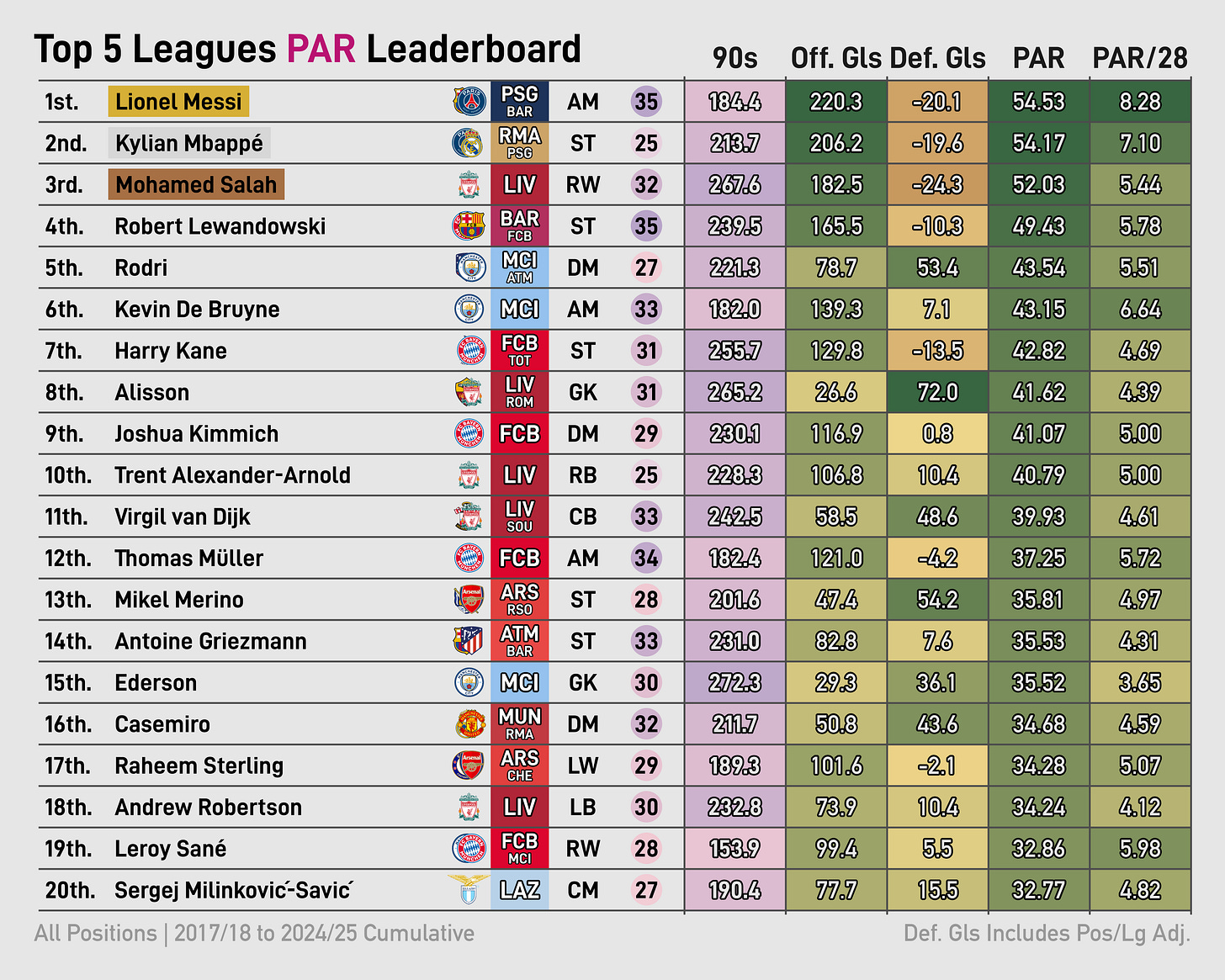

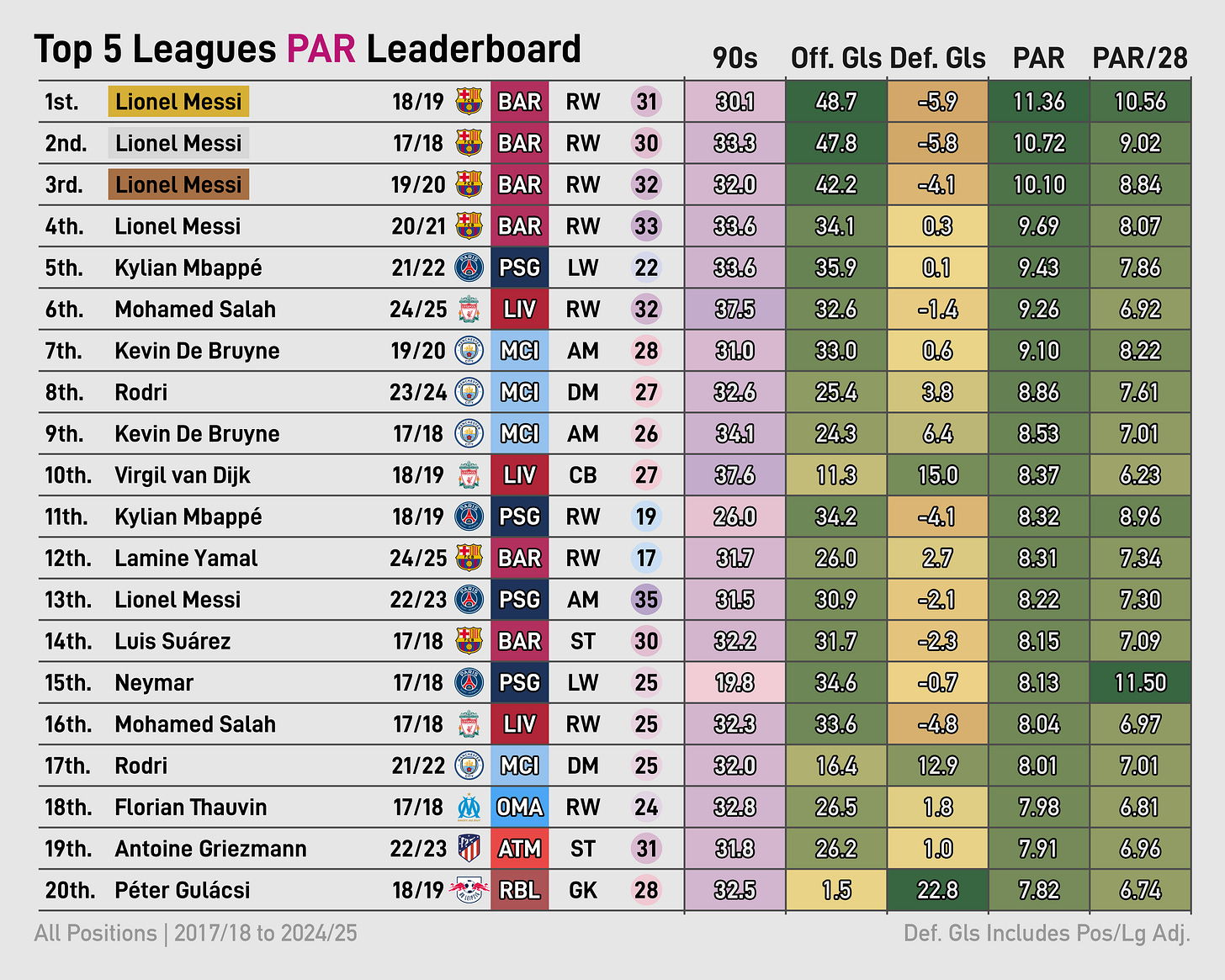

I’ll start by showing PAR totals. The first table shows the top 20 in cumulative PAR in the data era and the second table shows the top 20 PAR seasons in that span.

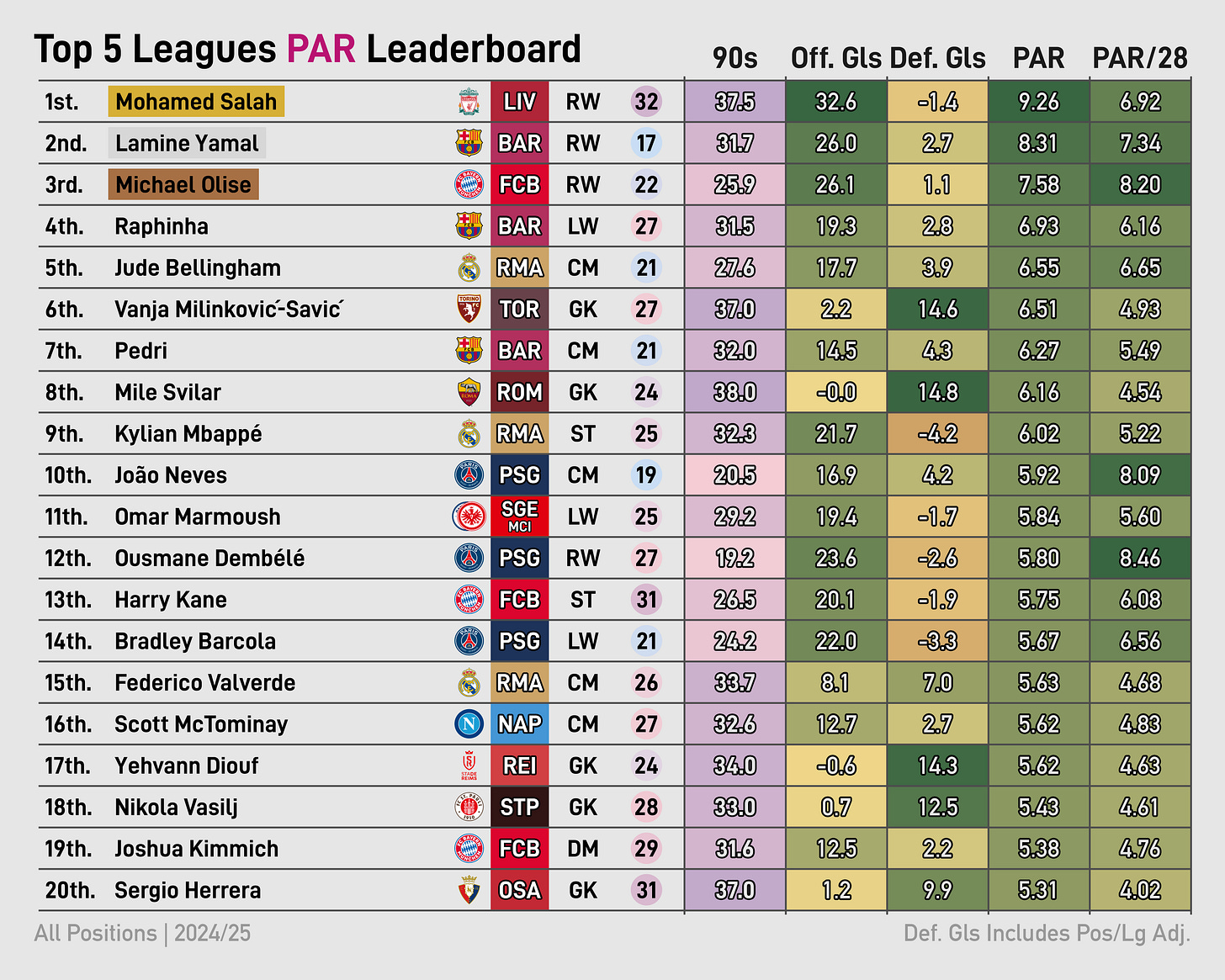

Here’re the totals for this past 24/25 season:

Lotta tables.

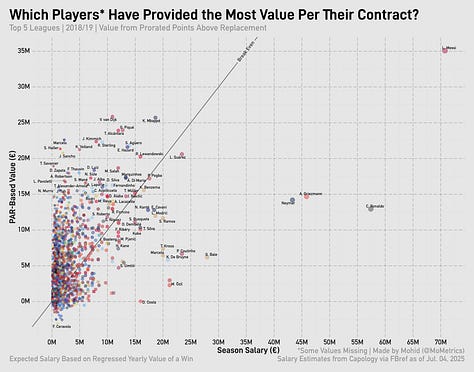

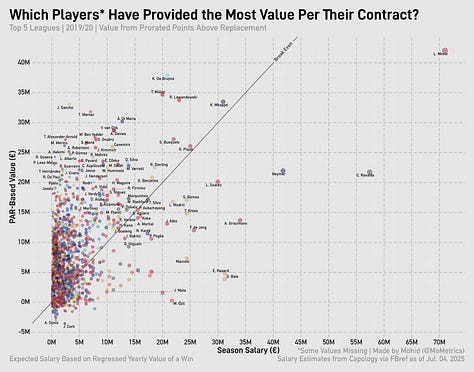

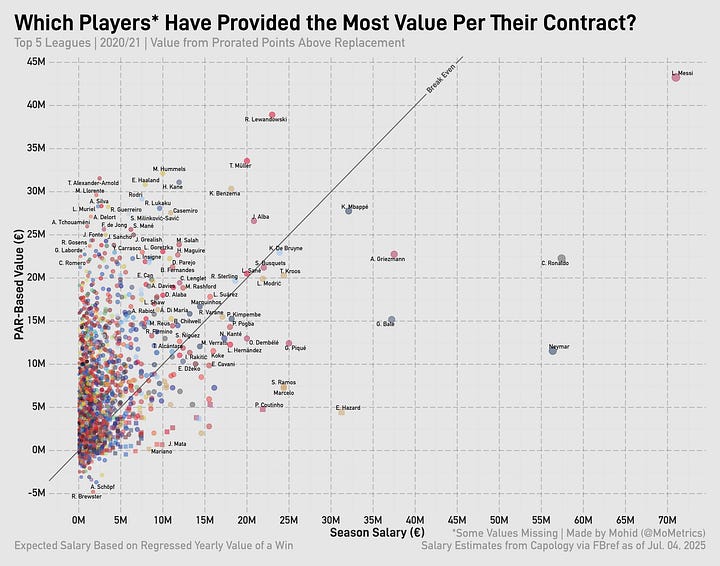

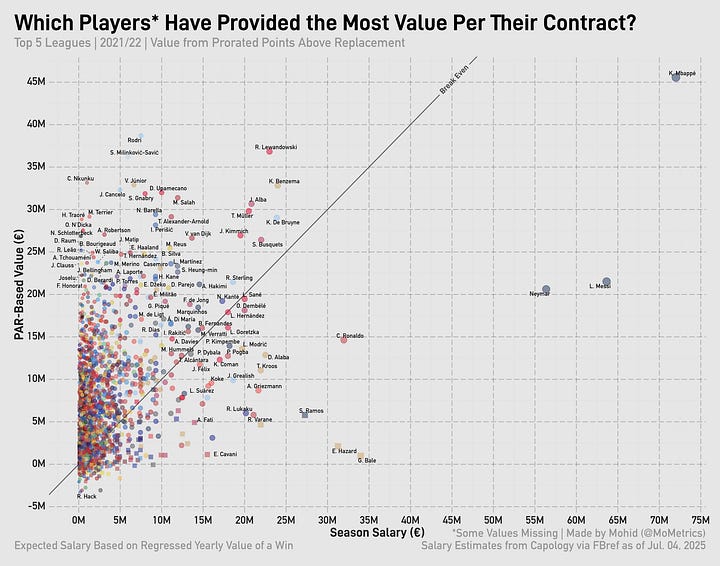

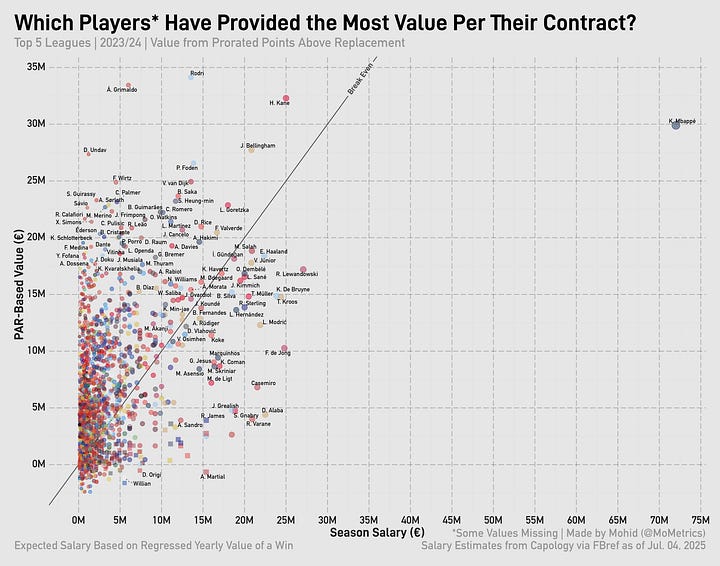

Taking our value per point above replacement and multiplying it by player PAR, we can compare it to the player’s actual salary for the season. First, though, I have to prorate player PAR to be per-38-games to equalize across leagues. Here’s that chart for 2024/25:

If a player’s above the diagonal line, they overperformed relative to their contract. If the player is below the diagonal line, they underperformed relative to their contract. The thing about using PAR is that negative values lead to ‘negative’ contracts on the y-axis—which, of course, doesn’t make real sense. That’s just an issue to live with, however.

Looking at the charts for the all the prior seasons, you can see how the most valuable player (usually Messi) is often ‘overpaid.’

That’s the core of the issue regarding ‘value’ from wins. By looking simply at the PAR of a player, you’re not incorporating all the other factors a player brings to the table. By signing Messi to a €71m/year deal after 2018, Barcelona were tying down the best player in the world and paying him for so many things: his loyalty, his marketing value, his legacy (5 Ballon d’Ors up to that point, another 2 to come at Barcelona), his output (beyond the box score), and his leadership.

Offense also tends to get paid more than other factors, meaning you’re more likely to be underpaid as a non-ST/AM/W. This makes sense, though, since offense tends to have a greater impact on points than defense8.

Going back up. Was Harry Kane overpaid in 24/25? Not by a long shot. This was a man who put up the third-best PAR total the year before and was top-15 for PAR that year. You’re willing to pay him as much as you do because of the value he’s brought and the value he will continue to bring (especially when you approach it from a relativity angle).

Lewandowski seems like a big overpay but he was Barcelona’s most valuable player on a title-winning side back in 22/23 and put up solid numbers in another title win 2 years later (8th highest amongst La Liga players in PAR in 24/25—7th amongst outfielders).

Haaland finished second in Ballon d’Or voting just two years ago and is arguably a top-15 player in the world at the moment. Though he’s been trending down for two seasons in a row…

Injuries will also tank the expected vs. actual salary amounts. David Alaba is the perfect representation of this phenomenon.

Final Evaluation

You can’t project a player’s summed value with just one statistic. PAR is good for assessing a player’s on-pitch value and influence but it doesn’t include every other factor that goes into a player’s contract discussions.

PAR is also limited in that it depends on goal contributions (even if VIBES and my Estimated Defensive Impact stats try to help boost players who don’t have that many goals and assists).

It’s also very hard to estimate the value of a point. Even I’m not satisfied with what I’ve settled on above. What I think could potentially have some value is if I prorated the NBA’s ~$5b salary to 96 teams (~$16b) and then divided that by all points above replacement-level to find the value of a win if football had concentrated salary like the NBA and if the top 5 leagues were a closed market (which would raise the value of any individual player—if you can't go looking outside the market, a player’s value goes up—plus there are a lot more football players out there than any other sport).

Soccer is a complex game besides all that, too. One player is unlikely to have as much influence on a win/point in this sport than in basketball or even baseball.

Basically, everything here means that all I’ve done regarding point evaluation doesn’t really matter and ultimately doesn’t mean much. PAR is good though. Trust that.

Note: I didn’t cover goalkeeper value because that’s an even more complex issue than outfield evaluation.

I’ve made some adjustments to reported salaries, particularly Mbappé’s 21/22 PSG salary and Frenkie De Jong’s salary at Barcelona post-COVID. These are minor changes that shouldn’t alter the results too much.

Valuation of Indirect Action-Based Effect on Estimated Scoring

Which are players who’ve played at least 25% of available minutes for the team (in the league, as always).

The way football uses points (W = 3, D = 1, L = 0) messes with these interpretation, a little bit. What we can assume is that draws = losses and so if you win 50% of your games, you get 50% of points—which is what makes the 23/114 thing work here.

Which I calculate through a simple Monte Carlo simulation using xG data per game.

This is annual salary for outfield players, only. I’d include GK information but they’re a special case when it comes to evaluation.

I’m missing four teams because FBref doesn’t have their full data: Hannover 17/18 & 18/19, Leganes 17/18, and La Coruña 17/18. This shouldn’t change the data too much but I want to make sure to clarify.

Change in xG per Game from year to year has a bigger impact on change in Pts per Game when compared to change in xGA per Game.